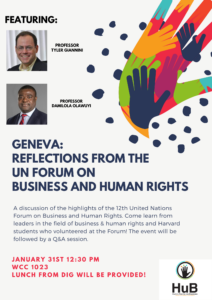

What a fabulous opportunity to hear Harvard Law School Professor Tyler Giannini, Clinical Director of the Human Rights Program-Harvard, and his former student, Harvard Alum Professor Damilola S. Olawuyi, SAN, FCIArb, speak at the Harvard Human Rights and Business Association event, with Mohini (Mo) Tangri moderating:

GENEVA: REFLECTIONS FROM THE UN FORUM ON BUSINESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS

Professor Giannini opened with a brief history of the the legacy of John Ruggie, one of the architects of the United Nations Global Compact, as well as of the Millennium Development Goals, the precursor of the Sustainable Development Goals. In 2005, then Secretary General Kofi Annan appointed Ruggie as the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights. In that capacity, Ruggie developed a set of principles, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which the The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) endorsed unanimously in 2011.

Giannini’s talk was followed by a short presentation by Elena Athwal on the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights 12th Annual Forum, in which she moderated the first ever Global Youth Panel, featuring youth activists from around the world, including:

Deives Picáz

Caroline Lichuma

Mihail Platinda

Shivani Agarwal

Oswald Anonadaga

and Pornchita (Duang) Fapratanprai

We were then joined by Professor Damilola S. Olawuyi, SAN, FCIArb (currently on a country visit to Morocco!) who discussed the mandate of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, which includes the Annual Forum, established by the Human Rights Council in 2011, and which has become the world’s largest global gathering on business and human rights, with over 4000 participants this past November. The UN WGBHR’s mandate as outlined in resolution 17/4, involves promoting and implementing the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, supporting capacity-building, advising on legislation related to business and human rights, conducting country visits, enhancing remedies for human rights affected by corporate activities, integrating gender perspectives, and coordinating with various international bodies and organizations. Additionally, per resolution 35/7, the Working Group is tasked with considering the implementation of these principles in the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The session was expertly moderated by our gracious host, Mohini (Mo) Tangri.

We are so grateful for the time given to us by our esteemed speakers, Professor Giannini and Professor Olawuyi, and very much look forward to more exciting engagements in the coming spring term!

A huge thank you goes out to the incredible work of the HuB team in putting this all together, and making it such a great success! 😍

Mohini (Mo) Tangri

Ivana Anna Nikolic

Jessie Hsia

Begüm Acar

Kayla Lee

Salomé Van Bunnen

Anastasiya Donets

Zohaib Babar

and Yuxin Zhang.

(Post author: Elena Athwal)

In the end of November, four board members of HuB will attend the 12th United Nations Forum on Business and Human Rights.

The UN Forum is the world’s largest annual gathering on business and human rights with more than 2,000 participants from government, business, community groups and civil society, law firms, investor organizations, UN bodies, national human rights institutions, trade unions, academia and the media.

Over three days, participants take part in 60+ panel discussions on topics that relate to the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework), as well as current business-related human rights issues.

The Forum is the foremost event to network, share experiences, and learn about the latest initiatives to promote corporate respect for human rights.

HuB board members will gather information on the recent developments in the filed of Business and Human Rights, and what lies ahead, and share that experience on campus in the beginning of 2024. Stay tuned!

Talk with Paul Hoffman – October 27, 2023

In late October 2023, the HuB co-organized an event with, inter alia, the Harvard Law School Human Rights Entrepreneurs Clinic and the Harvard Human Rights Journal. The organizations welcomed Paul Hoffman, a leading human rights litigator, to campus to discuss the recent 9th Circuit decision in Doe v. Cisco.

In July, the 9th Circuit allowed a case to proceed against Cisco Systems, Inc. for the company’s role in designing and implementing the “Golden Shield,” a security system which Plaintiffs allege facilitated the Chinese Communist Party’s surveillance, detention, and torture of Falun Gong practitioners. Among the claims allowed to proceed are several made under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS). Mr. Hoffman litigated and argued Cisco, along with the ATS case Doe v. Nestle, decided by the Supreme Court in 2022.

Mr. Hoffman discussed the Cisco decision in a post-Nestle landscape, including both the case itself and its implications for future human rights litigation in U.S. courts.

At this exciting event, we heard from current members of the HLS Community about their work related to human rights and business. These short Ted Talk style presentations covered personal experiences working with ESG, EU Regulation, human rights in different countries, and more.

With Mohini Tangri, Toon Dictus, Hina Uddin, and Sudheer Polaru.

BHR Through a Gender Lens

By: Johanna Lee (HLS J.D. Candidate, Class of 2021)

Posted: 4/8/2019

As part of the United Nations (UN) Forum on Business and Human Rights held last November, the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights (BHR) convened a Gender Roundtable for feminist and BHR practitioners to gather information on the unique challenges women and girls face with regards to business-related human rights abuses. One of the Roundtable participants, Ms. Irit Tamir, Director of Oxfam America’s Private Sector Department, came to Harvard Law School on April 1 to speak at the event “Business and Human Rights: Through a Gender Lens,” alongside Ms. Jane Nelson, Director of Corporate Responsibility Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). Co-hosted by Harvard Women’s Law Association (WLA) and Human Rights and Business Student Association (HuB), the event aimed to highlight the much-needed feminist approach to corporate accountability and BHR. Below are a few highlights from the event.

The Historical Arch of Corporate Accountability, BHR, and Gender

According to Ms. Nelson, there have been three phases of the corporate accountability and BHR movement. The first phase followed the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, focusing on the issue of compliance by corporations, in which workplace diversity became a part of businesses’ legal compliance measures. In the mid-1990s, the second phase emerged and was characterized by awareness raising. Former First Lady Hillary Clinton symbolically laid the groundwork on making human rights a global issue and a business issue in her speech “Women’s Rights are Human Rights,” which she delivered at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995. In the years to follow, the endeavor to raise awareness about the role of business in human rights abuses proved successful. This was in large part thanks to the combined efforts of the media and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like Amnesty International and Oxfam in bringing to light the human rights violations caused by extractive industries and the garment industry. For example, the negative press regarding oil spillages in Nigerian villages in 2005 resulting from Shell’s petroleum production in the Niger Delta caused a significant backlash against Shell.

The third phase developed in the early 2000s, as human rights advocates began to supplement their strategy of awareness raising to contending that corporations themselves had to do more to address human rights violations and become a part of the global solution. One of the earliest signs of this shift was the UN Global Compact, a non-binding corporate social responsibility initiative launched in 2000 that encouraged businesses to adopt ten principles in the areas of human rights, labor, the environment, and anti-corruption.

In 2009, the need to incorporate a gender lens to corporate accountability and BHR became apparent, as the UN adopted the Women’s Empowerment Principles, which offers a business case for corporations to simultaneously improve their bottom line while promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment. Since 2010, the gender lens for BHR has expanded, with the focus shifting beyond examining corporate boards and employees to examining the gender dimensions of supply chains. Several effective campaigns have been waged, including Oxfam’s “Behind the Brands” campaign, which began in 2013 and introduced the idea of rating major food and beverage companies based on their social and environmental policies and practices. That same year, Oxfam also began to look at the role of women farmers in cocoa supply chains. The NGO sought to persuade major companies such as Nestlé and Mars to enact policies to help empower women farmers who are significantly disadvantaged because they often do not hold title to the land they cultivate; are not members of farmer cooperatives; and do not have access to training, seeds, or credit. Examples of policies recommended by Oxfam include ensuring that women have access to training and pressuring governments to abolish discriminatory policies that prevent women from owning land.

Other recent phenomena that have helped strengthen the current movement to approach BHR through a gender lens include the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the #MeToo movement. Inaugurated in 2015, the SDGs have illustrated that efforts to combat poverty must necessarily entail measures to empower women and girls. Meanwhile, the #MeToo movement, which spread across social media in 2017, has helped shine a spotlight on issues that disproportionately impact women, ranging from sexual harassment in the workplace in the United States to gender-based violence in global supply chains.

Current Efforts to Promote a Gender Approach to BHR

Efforts by Oxfam and HKS

Despite the progress that has been made, Ms. Nelson stated that “there is still a long way to go.” The main problem is that of changing corporate culture. To address this issue, Oxfam is currently engaged in several corporate campaigns to promote women’s empowerment. For example, in 2018, Oxfam launched the new campaign “Behind the Barcodes,” which looks at the role of women in global supply chains. In addition, Oxfam has partnered with Mars to provide living incomes to farmers and empower women in their supply chains. Oxfam has also targeted pharmaceutical companies for tax evasion, which has increased drug prices and impeded women’s ability to access health. Moreover, Oxfam manages an activist fund, in which the NGO holds stock in companies that it is trying to influence. Meanwhile, HKS’ Corporate Responsibility Initiative encourages large multi-national corporations in “embedding and spreading” both the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the SDGs. The Initiative also strives to work more in collective action with civil society to set human rights standards for corporations.

The UN Gender Roundtable

The purpose of the UN Gender Roundtable held last November was to gather information on the impact of businesses on women in advance of a report to be published this June. According to Ms. Tamir, who participated in the session on Trade, Investment, and Tax, a wide range of subjects were deliberated. These include the gender dimension of State investment policies and budgeting, which often disregard the needs of women; the issue of unpaid care and the negative cultural norm created when companies only provide maternity leave; and the pervasive problem of violence against women. The Roundtable also included discussion of the creation of a binding treaty on the UN Guiding Principles and the recent demands of feminists to more prominently highlight gender in the treaty language. While the Roundtable exhibited a new drive to apply a feminist approach to corporate accountability and BHR, it remains unclear how the discussion will translate to concrete action, considering that the Working Group is an unfunded UN mandate.

Efforts by Corporations

How have corporations themselves begun to address the increasing demands to account for gender in BHR? First, companies have begun to examine their core business operations beyond basic compliance concerns to strategic risk management issues. Specifically, companies have begun to assess their due diligence measures at the workplace by critically thinking about the existence of unconscious gender biases in the office, how managers are evaluated, whether the company has established specific gender targets, and whether women have access to grievance mechanisms in the case of abuse. Second, companies, especially those involved in agrobusiness, have looked beyond promoting women’s inclusion and empowerment at the workplace to their supply chains more broadly. Third, more companies have begun to engage in collective action around human rights advocacy, such as by speaking up about corporate tax avoidance and promoting a human rights and gender-based approach to investment. Such progressive steps taken by companies reveal a promising, gradual convergence of the business and human rights agendas.

Conclusion: What’s Next?

The BHR field has, until recently, largely overlooked the unique needs of women and girls. In order to address this gap, the following actions must be taken. First, social and cultural norms must shift so that human rights and gender concerns are always embedded in corporate and government policies and practices. Second, governments should increase regulation of companies by imposing disclosure requirements. Third, companies should pressure governments to establish policies that remain obstacles to women’s empowerment (e.g. policies that prevent women farmers from owning land). Fourth, the investor community should utilize gender indexes in order to only invest in socially responsible corporations that respect human rights and promote gender equality. Fifth, academics and activists should combine forces to approach BHR using a gender lens.

Overall, it is clear that in order to most effectively promote BHR and women’s empowerment, civil society must engage corporations and support policies that will simultaneously serve business interests and advance human rights. By joining efforts, BHR advocates, corporations, and governments will be able to shape corporate behavior in a way that promotes women’s inclusion and empowerment.

Human Rights in Food Justice – Labor & Global Supply Chains

By: Johanna Lee (HLS J.D. Candidate, Class of 2021)

Posted: 3/11/2019

On March 9, 2019 Harvard Human Rights and Business Student Association (“HuB”) co-sponsored Harvard Law School’s 2019 Food Justice Symposium. Keynote speaker Conniel Malek, Director of True Costs Initiative, introduced the theme of “embracing complexity” in food systems. To highlight this complexity, the Symposium presented a diversity of approaches to promoting food justice through its four panels. The final panel, titled “Hidden Costs: Labor and the Global Supply Chain,” was co-moderated by HuB Treasurer, Alexander Kontopoulos, and featured four experts in the field. Each panelist brought a unique approach and set of experiences to the conversation on how workers, corporations, and large lenders can promote sustainable environmental and labor practices in global supply chains.

Charity Ryerson, Founder and Legal Director of Corporate Accountability Lab, began the session by explaining the importance of remediating corporate abuses and asserting that there are “no rights without remedies.” To illustrate her point, she discussed Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa sector, in which multi-national companies make major profits, yet farmers do not make enough to pay for workers. As a result, farmers are unable to purchase basic necessities and rely on child or forced labor. The solution to this problem, according to Ryerson, is not corporate social responsibility (“CSR”)—which often only serves as a public relations (“PR”) tool for corporations and fails to impact conditions on the ground—nor is it is punishing cocoa farmers for their reliance on cheap or free labor. Instead, the key is to allot a greater profit margin to farmers, a solution complicated by low, government-set prices and willful blindness to child labor by civil society. Indeed, one major reason that West Africa produces seventy percent of the world’s cocoa supply is the exceedingly low prices set for cocoa.

Next, Malek discussed how corporate accountability alone is not sufficient in ensuring food justice. Instead, strong rule of law and enforcement are crucial. To achieve this, Malek highlighted the importance of entering the food justice space and talking to and learning from one another. She explained how she seeks to engage with advocates who use different types of tactics to pressure corporations, whether it is via the media, campaigns, or research. It is the convergence of these leverage points that shifts the cost-benefit analysis of corporations sufficiently to change their behaviors. Without such concerted, sustained, consumers will remain unaware of the “true costs” of the food they purchase and instead continue to be inundated with glamorous CSR campaigns.

The following panelist, Suzanne Adely, Regional Organizer for Food Chain Workers Alliance, focused on the challenges faced by food workers, who constitute fourteen percent of all workers. While supplying the country’s food supply, these workers experience the greatest food insecurity, earn the lowest median wages, and have very low job security. Adely explained the historical and structural roots of such exploitation, connecting the displacement of Native American food systems with slave labor and indentured servitude, systems that modern American society has inherited. This legacy appears in the United States today in the exploitation of immigrant labor and workplace raids at farms and meatpacking factories by government agents. Ultimately, Adely concluded that the most effective solution to holding corporations accountable is to empower workers to organize so that they can place real economic pressure on their employers and require them to make substantive changes. Another strategy is to build alternative models of food production, such as the creation of cooperatives.

Finally, Frazer Lanier, Vice President of Environmental and Social Risk Management at Citi, expounded upon Citi’s efforts to address labor rights concerning palm oil. Lanier highlighted the power of using financial leverage through system of lending to hold corporations accountable. He explained that in order to be qualified for loans, Citi clients must be certified by the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil (“RSPO”), which lays out various conditions in loan agreements. Examples include prohibiting a quota system, which often leads to entire families, including children, to work on the plantation; barring the confiscation of passports; mandating a living wage for all workers; and applying new technologies, like Ulula, an SMS system that obtains anonymous feedback from workers regarding labor conditions. The violation of such principles results in suspension of RSPO certification, which Lanier maintained has significant repercussions for the palm oil seller since certification is required for market access in a number of countries.

While the mechanism of loan conditions shows some promise for tackling issues that may emerge going forward, an audience member noted that such programs have been heavily criticized for failing to address historical dispossessions of indigenous lands. In response, Frazer pointed to the RSPO’s grievance mechanism for handling complaints, including those filed by indigenous people. Ryerson also mentioned the potential for employing contract law as an additional avenue of redress outside the RSPO. The inclusion of so-called “third party beneficiary” language in a contract explicitly grants individuals who are not parties to the contract the right to sue. This means that if a loan or supplier agreement is conditioned on meeting certain labor or environmental standards, then failure to meet those standards would constitute a breach of contract, thus permitting workers—as third party beneficiaries to the contract—to sue in the country where the lead firm operates. This mechanism, as opposed to voluntary initiatives, shows more promise for ensuring a remedy to human rights violations.

The issues discussed at the Symposium honed in on the complexity of our current food system, including the social injustices deeply embedded in the global supply chain. Rather than shying away from the difficult challenges raised or suggesting “silver bullet” solutions, the panelists affirmed the need for diverse and nuanced approaches to effectively alter the prevailing economic and legal landscape. For example, they showed that it is not enough to simply raise the cost of chocolate bars; instead, there needs to be a fundamental shift in the distribution of wealth, increasing the earnings of farmers, instead of corporations. Likewise, while the development of messaging systems that anonymous survey workers is a promising start, supporting infrastructure must be established in order to ensure that the communications are sent without coercion. This realistic portrayal of the problems facing the modern food system combined with the auspicious showcase of the possibility of creative solutions to such dilemmas assuredly left Symposium attendees with a sense of optimism regarding the future of food justice.

Recent Comments