Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

*Sudiksha Dhungel

Abstract

Cultural heritage is more than artifacts or traditions; it is the silent but profound testament to a community’s identity, struggles, and resilience. “Engraved in Blood” symbolizes the sacrifices made throughout history to preserve this legacy, often in the face of adversity. This article delves into the intricate relationship between cultural heritage and human rights. It emphasizes the importance of recognizing cultural heritage as an inalienable human right and provides actionable solutions for its preservation. The findings highlight the socio-legal challenges that cultural heritage faces, from globalization and conflicts to cultural appropriation and neglect. Practical implementations proposed include policy reforms, increased community participation in heritage conservation, and the integration of educational initiatives to foster awareness and engagement in its protection. While focusing on the Indian socio-legal context, the research reflects on the delicate balance between modernization and heritage preservation, along with the evolving legal frameworks addressing these issues. Socially, this paper advocates for enhanced recognition of cultural heritage role in shaping identities and fostering societal cohesion. Ultimately, the article envisions cultural heritage as a bridge between past and future, reflecting shared histories and collective aspirations.

Introduction

Cultural heritage is not just a relic of the past but a living, breathing testament to human existence. It acts as a link between our ancestors, the present, and the future by encapsulating the tales, hardships, and triumphs of many generations. The threads that weave cultural history into the fabric of identity are increasingly in danger of fraying in a society that is modernizing at a rapid pace. “Engraved in Blood” reflects this profound struggle, representing the generations that fought—sometimes at tremendous personal cost—to preserve their cultural heritage. This essay investigates the complex relationship between cultural heritage and human rights, contending that heritage is not a privilege but an essential right. By addressing socio-legal issues and suggesting practical answers, it emphasises the critical necessity to conserve cultural heritage in an era of fast modernisation and globalisation.

This article seeks to explore the intricate interplay between cultural heritage and human rights, positing that heritage is not merely a privilege but an inalienable right. It analyzes the socio-legal difficulties that endanger cultural heritage and emphasizes the importance of protecting it in order to maintain societal cohesiveness and identity. With an emphasis on practical solutions, this article emphasizes the need for combining educational activities, policy reforms, and community involvement to maintain this precious legacy. The Indian socio-legal setting serves as a focal point, demonstrating the delicate balance between legacy preservation and modernity, with far-reaching consequences for global frameworks. Finally, this article hopes to motivate a community effort to acknowledge and advocate for the protection of cultural heritage as a fundamental human right.

Conceptual Framework

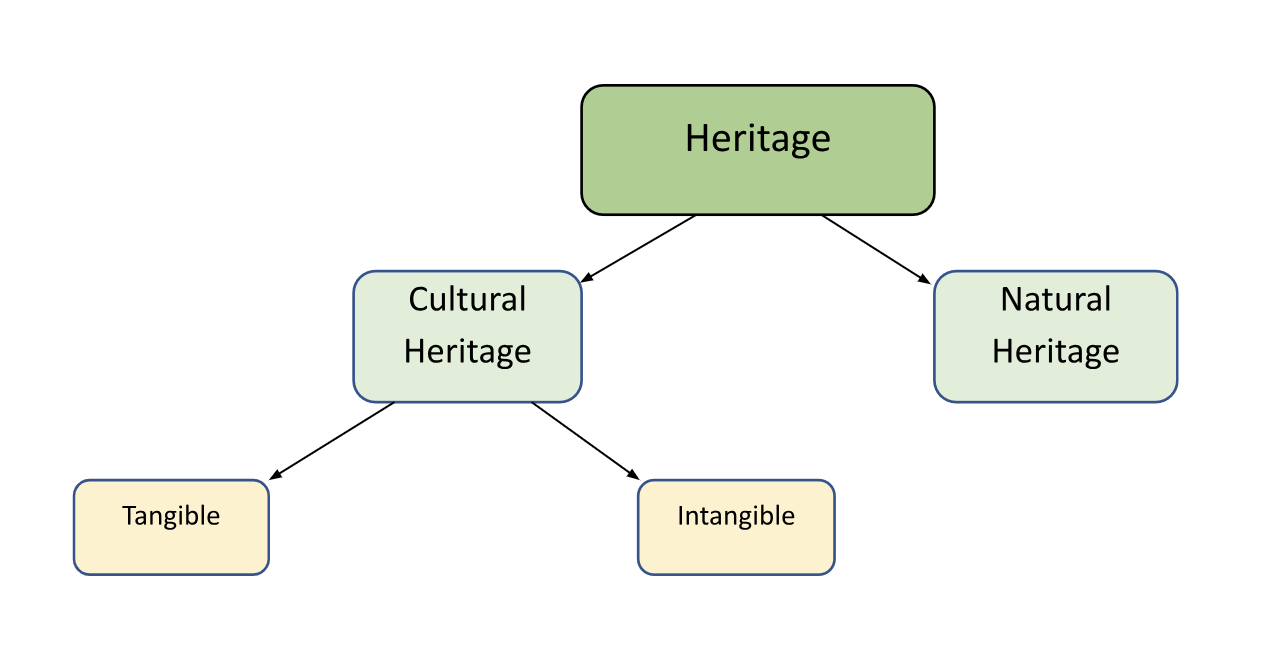

Cultural heritage, in its essence, embodies the legacy of a community, encapsulating both tangible and intangible elements that define its identity. Tangible cultural heritage refers to physical manifestations such as monuments, artifacts, historical buildings, and archaeological sites, which stand as enduring symbols of human creativity and historical significance.

On the other hand, intangible cultural heritage encompasses non-physical attributes, including traditions, oral histories, languages, rituals, and knowledge systems. These intangible aspects are vital as they carry the living traditions of a community, fostering a sense of continuity and connection across generations.

Cultural heritage is closely tied to human rights, as protecting it ensures the fundamental right to participate in and enjoy one’s culture. Human rights instruments like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) highlight cultural rights as vital for dignity and identity. Recognizing cultural heritage as a human right helps preserve unique identities and promotes a diverse global society.

Cultural heritage shapes individual and collective identities, fostering belonging and societal cohesion. It connects the past with the present and strengthens intergenerational bonds, making it crucial in maintaining diversity and cross-cultural respect in an increasingly globalized world.

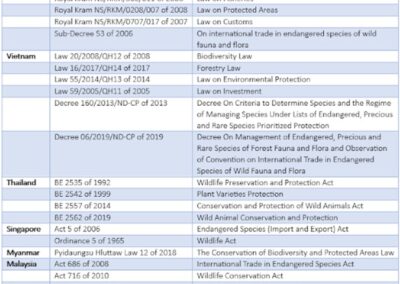

International conventions, like the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Convention and national laws work to protect cultural heritage, but challenges remain in enforcement, adaptation, and addressing issues like cultural appropriation and neglect.

Socio-Legal Challenges to Cultural Heritage

Cultural heritage faces significant challenges in a globalized world. While globalization fosters connectivity, it also brings cultural homogenization, overshadowing unique traditions. Conflicts and wars exacerbate this issue, with cultural artifacts getting targeted and destroyed, as seen in- Syria and Iraq. Looting and trafficking further deprives nations of such history. These difficulties are not only cultural or legal; they exist at the crossroads of law and society, making them socio-legal in nature. The word “socio-legal” refers to how legal frameworks interact with cultural, social, and political realities, determining whether legacy is safeguarded or neglected. While laws may technically protect cultural sites and practices, their success is frequently dependent on enforcement, public awareness, and government priorities.

Cultural appropriation and neglect are subtle yet harmful threats to the preservation and authenticity of cultural heritage, as well as the cultural identity of the communities that maintain these traditions. Cultural appropriationoccurs when components of a culture, such as traditional clothes, rituals, or art, are commodified or exploited without proper acknowledgement, resulting in the loss of their original value. For example, indigenous fashion designs and spiritual practices such as yoga are sometimes commercialized without regard for their origins. Neglect, on the other hand, results from a lack of priority, which causes cultural sites to deteriorate, languages to die, and traditional crafts to decline. Cases such as the fading away of Ainu language in Japan and the erosion of Harappan archeological sites show how neglect may destroy cultural identity over time. Additionally, neglect due to lack of prioritization leads to the deterioration of cultural sites.

The most complex challenge to cultural heritage conservation is balancing modernization with heritage preservation. Urbanization and technical improvements frequently collide with the urge to preserve cultural identity, as growing cities, infrastructure projects, and commercialization endanger heritage sites and traditional customs. Finding a balance between these competing goals necessitates creative solutions, such as using sustainable materials in restoration, utilizing modern tools like 3D scanning for documentation, and incorporating heritage conservation into urban planning. Inclusive planning guarantees that local people, historians, and policymakers all participate in decision-making, preventing cultural oblivion. Respect for the past entails recognizing the historical and cultural relevance of heritage places and traditions while assuring their preservation without jeopardizing authenticity.

Enhanced Approaches to Cultural Heritage Preservation: Policy, Community, and Innovation

Policy Reforms for Stronger Legal Protections of Cultural Heritage

In order to ensure the safeguarding of cultural heritage, robust legal frameworks must be established, as existing safeguards are frequently undermining by lax enforcement, legal loopholes, and insufficient international cooperation. While the UNESCO conventions establish worldwide standards, they lack binding enforcement measures, allowing illicit trafficking and destruction to continue. National laws, such as India’s Antiquities and Art Treasures Act (1972), also face challenges due to inadequate monitoring and bureaucratic delays, resulting in continuous smuggling and uncontrolled development near heritage sites. These legal structures must be bolstered by stronger regulation, additional funding, and improved integration of community engagement in preservation activities. UNESCO agreements play an important role in encouraging governments to establish comprehensive policies, but without improved domestic implementation and international collaboration, cultural heritage is subject to exploitation and neglect.

Community Participation in Preservation Initiatives

Cultural heritage preservation cannot succeed without the active involvement of local communities. By engaging the people who live within and around heritage sites, preservation efforts gain authenticity and relevance. Empowering local communities to take ownership of their cultural heritage helps ensure its protection for future generations. Numerous case studies have shown that community-led initiatives, such as the Luk Lan Muang Phrae project in Thailand, which revitalized traditional crafts through local engagement, and the Haida Gwaii Watchmen program in Canada, where indigenous stewards protect and educate visitors about sacred heritage sites, can resurrect long-forgotten practices.

Integration of Educational Programs to Raise Awareness about Cultural Heritage

One of the most effective ways to ensure long-term preservation is to cultivate an understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage among younger generations. Schools and universities can integrate heritage education into their curricula, helping students to value and protect cultural landmarks and practices. Public awareness campaigns also play a crucial role, providing platforms for discussions on the importance of preserving heritage in the face of rapid modernization.

Leveraging Technology to Document and Protect Heritage

In today’s digital age, technology serves as a powerful tool in heritage preservation. Digital documentation, including 3D scanning and virtual tours, allows for the preservation of cultural sites in their current form, mitigating the risks posed by natural disasters or urban development. Technologies such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are also used to map and monitor heritage sites, ensuring their continued protection.

A critical analysis of the Indian socio-legal framework for cultural heritage preservation.

Historical Sacrifices Made to Protect Indian Cultural Heritage

Throughout India’s history, various communities have made immense sacrifices to protect their cultural heritage. The struggle to safeguard ancient temples, manuscripts, and rituals has been ongoing, often in the face of colonial exploitation and modern encroachment. Movements like the conservation of the Sanchi Stupa or the protection of Vedic manuscripts from looting demonstrate the resilience of Indian society in preserving its cultural identity.

Current Legal Frameworks and Their Limitations

While India has a robust set of legal protections for its cultural heritage, including the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (1958), enforcement remains a challenge. Issues such as bureaucracy, lack of funding, and insufficient penalties for violations have hampered the effectiveness of these laws. Furthermore, the complex legal structure often creates confusion about ownership and rights, which can result in exploitation or neglect of cultural assets.

Case Studies Highlighting Successes and Challenges in Indian Heritage Preservation

One notable success is the protection of the Konark Sun Temple in Odisha, which was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Through collaborative efforts between the state, local communities, and international experts, this site has been preserved. However, challenges remain, such as the ongoing threats to the Taj Mahal from environmental degradation and illegal construction around heritage sites. These cases illustrate the complex nature of cultural heritage preservation in India, where success often relies on collaboration and sustained efforts.

The Evolving Role of Indian Society in Preserving Cultural Heritage Amidst Modernization

As India continues to modernize, the tension between progress and preservation becomes more pronounced. Urbanization, industrialization, and the rise of global consumer culture pose significant risks to heritage preservation. However, there has been a growing recognition of the need to protect cultural heritage, with Indian society becoming increasingly involved in efforts to safeguard its history. Initiatives like the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) have engaged the public in heritage conservation, ensuring that modernization does not come at the cost of cultural identity.

Broader Social Implications of Cultural Heritage Preservation

By reserving traditions, languages, and historical landmarks, societies pass on lessons embedded in their cultural identity-offering continuity in an ever-changing world. This sense of inheritance is vital for intergenerational equity, reminding us that the treasures we protect today are not merely relics but the legacy of tomorrow.

Moreover, cultural heritage serves as a powerful medium for cross-cultural understanding and global solidarity. In a world marked by increasing polarization, the appreciation of diverse traditions and practices fosters empathy, respect, and collaboration. Initiatives such as UNESCO’s World Heritage program exemplify how international cooperation can safeguard shared human history, strengthening the ties that bind us as a global community. However, this interconnectedness also places a moral obligation on societies. Preservation efforts must address social and ethical responsibilities by being inclusive and respectful of marginalized voices. These efforts require careful consideration of whose heritage is prioritized, how it is represented, and how to ensure its meaning is not diluted or exploited for commercial gain. Ultimately, cultural heritage preservation is not simply about protecting artifacts or sites, it is about honoring the values, identities, and histories they embody, ensuring that they continue to inspire future generations.

Recommendations and Future Directions

Preserving cultural heritage in a modernizing world requires bold and innovative steps. Strengthening laws and policies, both internationally and domestically, is essential. Treaties like the UNESCO Convention should be enforced more effectively, through more robust sanctions for infractions, enhanced international collaboration, and more stringent compliance monitoring. This would entail real-time monitoring of illegal trafficking networks, increased funding for heritage protection initiatives, and required reporting on conservation efforts. Furthermore, binding legal mechanisms that mandate signatory nations to act quickly to prevent encroachments, illicit trafficking, and the destruction of heritage sites could be implemented by UNESCO and national governments. To guarantee the ongoing preservation of cultural assets, governments must also strengthen sanctions, fill legislative loopholes, and enhance funding.

Connecting people to their heritage is equally important. Schools can teach heritage studies, and community events like storytelling, heritage walks, and workshops can make preservation engaging and relevant. Digital tools like IoT (Internet of Things) frameworks, virtual reality tours, and online archives can monitor sites and bring heritage to a global audience.

Sustainability is key to ensure the long-term protection of cultural assets while tolerating modern development. Practices like adaptive reuse, eco-friendly restoration, and community-driven upkeep can balance conservation with modernization. Interdisciplinary collaboration between experts, policymakers, and communities can create innovative solutions for challenges like urban encroachment and climate change. By embracing technology, sustainability, and collective effort, we can ensure that cultural heritage thrives in today’s world and for generations to come. Additionally, virtual reality tours, 3D documentation, and online archives can engage a global audience while preserving sites at risk of destruction.

Conclusion

Cultural heritage is more than just a collection of artifacts, traditions, or landmarks; it is a bridge between the past and the future, forged in the sacrifices, struggles, and unwavering spirit of those who fought to protect it. Every monument restored, every ritual practiced, and every story passed down carries the echoes of resilience and defiance, reminding us that heritage is not merely inherited; it is preserved through the strength and resolve of those who came before us.

As we navigate the challenges of modernization, globalization, and climate change, we must embrace cultural heritage as an inalienable human right. Its preservation is a shared responsibility, requiring the united efforts of communities, policymakers, and individuals alike. By valuing heritage not just as a relic of history but as a living testament to identity and humanity, we ensure that its essence endures, binding generations, fostering understanding, and inspiring a collective future that honors the legacy of the past.

*Sudiksha Dhungel is a law student with a keen interest in legal research, policy, and societal impact. Passionate about fostering intellectual discourse, she actively engages in academic writing, mooting, and initiatives that promote mental wellness, along with other meaningful discussions on contemporary legal issues. Committed to both scholarship and practical impact, she seeks to contribute to the evolving landscape of law and justice.