June 2025 – Muses of the Month

Musings of the Month – June 2025

At the dynamic crossroads of creativity and the law, there are countless voices shaping the future

of how we make, protect, and experience art. To celebrate and spotlight those voices, HALO is proud to launch Musings of the Month — a new monthly series designed to elevate diverse

perspectives all over the world in the domain of art law.

Each month, we’ll feature “Muses” — those who are inspiring, thoughtful, and influential —

from across the creative and legal fields. Our Muses may be legal scholars, academics, practicing attorneys, artists, curators, gallerists, art students, law students, or cultural stewards. Through essays, interviews, articles, or other short-form media, these contributors will explore a range of timely and timeless topics impacting art, culture, and justice.

We begin our series in June with a powerful lineup of contributors who reflect the spirit of this

project: interdisciplinary, forward-thinking, and deeply engaged.

This month’s artistic featured Muse is Richard Beavers, founder of the Richard Beavers

Gallery, a space dedicated to representing artists whose work reflects the African American

experience. In an intimate interview by our very own Shira Fischer, Beavers shares the story

behind building a gallery with a mission rooted in empowerment, education, and community

engagement — and what it means to support artists beyond the canvas.

Also featured in this inaugural edition are five authors whose written pieces dive into urgent

issues at the forefront of art law and cultural discourse:

• Sarah Conley Odenkirk reflects on the legal implications and challenges of AIgenerated

art and authorship;

• CPT Jessica Wagner, a legal officer with experience in cultural property protection,

examines military legal frameworks for preserving heritage in conflict zones.

• Professor Gilad Abiri explores the inadequacy of intellectual property with respect to

AI;

• Nia Coleman considers law’s role in the preservation of African cultural heritage and art;

• Dr. Sara Adami-Johnson discusses the challenges of AI creativity and the rapidly

developing legal landscape;

Through Musings of the Month, we hope to cultivate a space for reflection, dialogue, and

discovery — one that brings together the voices shaping the ever-evolving relationship between creativity and the law.

Join us each month as we amplify new musings from those thinking critically and passionately at the edges of art and legal practice.

Yours,

Renée Ramona Robinson

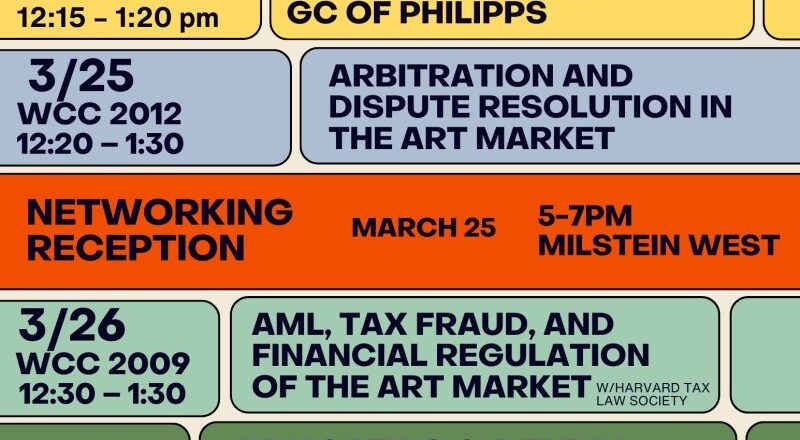

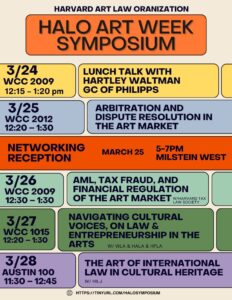

HALO Art Week 2025

April 11, 2025: How To: Mediate Art Law Disputes with Judith Prowda

Join HALO for our first installment of our “How-To” series with Judith Prowda, Faculty at Sotheby’s and founder of major art group, Stropheus Art. This talk will center on Judith Prowda’s work as an arbitrator and mediator in art law and commercial disputes.

In each “How-To” session, we will be exploring a particular aspect of art law practice taught by an art law practitioner.

The intent of the series is to teach students to acquire necessary skills and practices in their path to becoming an “art lawyer.”

Lunch will be provided!

WCC 1019

March 27, 2025: Navigating Cultural Voices, on Law & Entrepreneurship in the Arts

HALO x HALA x WLA x BLSA x HFLA

The Harvard Art Law Organization, kindly co-sponsored by Women’s Law Association, Harvard African Law Association, Harvard Black Law Students Association, and Harvard Fashion Law Association is excited to host three incredible female trailblazers in the art industry, Oyinkansola Dada, Tania Phipps-Rufus, and Tanya Layne, for what is sure to be a fascinating conversation on navigating legal and business complexities in the art world.

Our panelists—a gallery owner, a Chief Legal Officer, and a legal scholar—will delve into key legal challenges facing artists, galleries, and cultural institutions, from intellectual property protection and contractual negotiations to cultural property laws and ethical concerns in art transactions. We’ll also examine how legal frameworks shape artistic movements, impact marginalized communities, and adapt to technological advancements like NFTs. Please do not miss this unique event with these important voices, food will be provided!

Oyinkansola Dada is founder and gallery owner of Dada gallery and creator of Dada magazine. A qualified solicitor, she has achieved enormous success with constructing a space in which to champion underrepresented artists from the Black Diaspora in the art space.

Tanya Layne is the Chief Legal Officer of Gagosian. She not only worked in private practice, but has over ten years of experience at Sotheby’s as Senior Vice President and Associate General Counsel.

Tania Phipps-Rufus is a specialist in fashion law, intellectual property (IP), business, and cultural analysis, known for her comprehensive insights on legal trends, cultural shifts, and industry innovation. As a Senior Lecturer and course leader at the University of East London, she combines her background to explore critical issues at the intersections of contemporary culture.

WCC 1015